Their Eyes Were Watching God

Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston, first published in 1937, is an American classic that continues to top “best of” lists and remains a staple in university classrooms.

As Edwidge Danticat once said, it is a “brilliant novel about a woman’s search for her authentic self and for real love”. It is truly a gem of a book, one whose acclaim feels timeless.

And yet, I only read it for the first time this month. Like Hurston, I went to Barnard, and I’ll admit to feeling a little embarrassed that I hadn’t read her novel sooner. That said, I believe books enter our lives at the right time. I’m not sure I would have appreciated this story if I had been forced to read it in undergrad. Reading it now, in this season of my life, felt necessary and transformative.

Because this novel is a staple syllabus selection, I knew I didn’t want to read it alone. Rather than rush to finish it myself and then assign it to my book club, I suggested we read it together. And I’m so glad we did.

At first, I wasn’t sure how to facilitate that “togetherness.” I considered a group text, an Instagram channel, maybe even weekly emails. None felt quite right until one of our members suggested an app called Fable.

Fable is an app designed specifically for book clubs, where each chapter has its own chat thread for members to post thoughts and highlight passages. It’s designed for interaction and connection amongst book club members.

I wasn’t sure how many people would join on such short notice, but within a week, fifty people had signed up. I quickly found myself checking the app daily, posting my own reflections, and reading through others’. It’s an app I’ll definitely continue to use.

One of the topics we messaged back and forth about was Tea Cake’s character. I had always heard of him as Janie’s great love, so I was startled to read the moments where he steals her money and physically assaults her.

I texted into the chat: “Tea Cake is whipping Janie now?”

Responses came quickly:

- “Yeah… Tea Cake is supposed to be the good love story?”

- “I get people aren’t perfect, but dang.”

- “The behavior is normalized and Tea Cake feels threatened.”

- “Something makes me not trust Tea Cake, but I’m glad Janie seems so happy.”

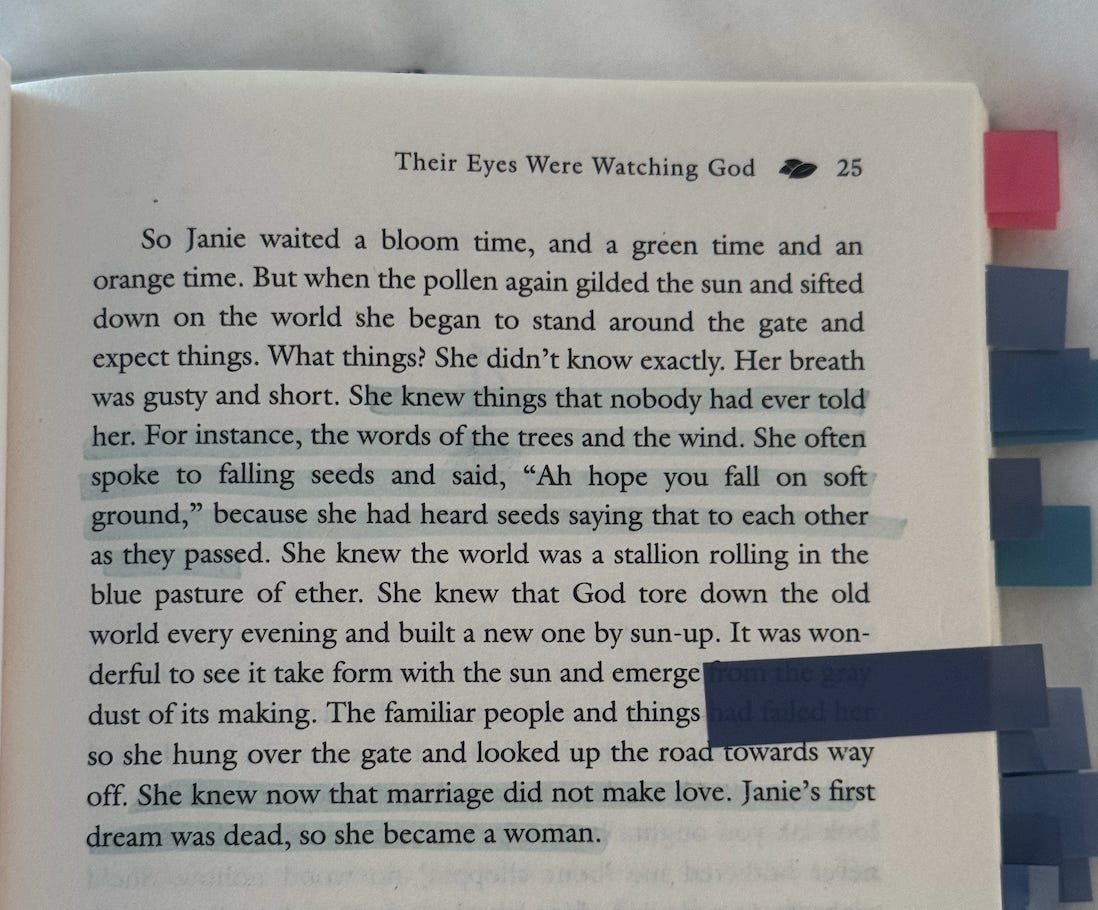

These responses both validated and challenged my instinct to immediately condemn him. As some pointed out, Hurston presents Tea Cake’s behavior within the norms of the time. The novel itself frames the act as “no brutal beating at all… just to show he was boss” (147). Given the social fabric, Tea Cake, having only hit Janie once or twice, is considered rare and even honorable. But from my modern perspective, any form of abuse is unacceptable. So I wondered, where is this loving Tea Cake everyone raves about?

And yet, Hurston complicates this picture by also showing Tea Cake’s tenderness. My favorite moment is when Janie wakes to find him brushing her hair, a gesture meant purely for her pleasure. He explains, “Ah been wishin’ so bad tuh git mah hands in yo’ hair. It feels jus’ lak underneath uh dove’s wing next to mah face” (103). This simple act means the world to her, and to us as readers. Not only does he show his mind’s desire to satisfy her, but he also directly soothes an insecurity of hers.

Hurston’s symbolism of Janie’s hair runs throughout the novel. Jody, jealous of the attention Janie receives, forces her to cover it. Tea Cake, by contrast, delights in it. Danticat reminds us that because of Tea Cake, Janie “experiences more freedom than most women of her time”. For Black women readers, the motif is heartwarming.

Tea Cake’s second act of devotion is the one that kills him. During the hurricane, he saves Janie from a rabid dog, sacrificing his own safety for hers. It’s a moment that cements his love for her.

These two contrasting moments carry significant weight in the novel. Does his tenderness and sacrifice outweigh the theft and abuse? It seems Hurston wants readers to share the same ambivalence that Janie feels.

It’s also crucial that Janie is the one who must end Tea Cake’s life. While the act is framed as merciful, it also propels her into her ultimate independence. By returning home alone, uninterested in remarrying and uninterested in others’ thoughts of her, Janie embodies the self-sufficiency she has long been seeking. In this way, Janie reads like a modern woman.

Reading this book in community made the experience unforgettable. It’s easy to see why the novel is so often assigned: it’s more than just “a portrait of Black life in the 20th century,” but a text overflowing with themes and conflicts that demand discussion.

Some of my lingering questions include:

- Why did Hurston choose this title? Why did she use their instead of her, or were instead of are? What kind of “God” is Hurston pointing towards?

- Are natural disasters meant to represent God, fate, or both?

- Who is Janie outside of her relationships? Does she make it to her truest self at the end?

- What do we make of Mrs. Turner’s explicit racism and colorism?

- Finally, where do we go from here? What does this novel still point us toward today?